Changing plans vs making plans.

A subtle, but helpful distinction.

I am a professional planner. I make plans.

What qualifies one as a professional might be material for another post.

A universal characteristic of plans is that they will change. Rather than be frustrated by this reality or abandon structure in the name of infinite agility, there’s a third way: Get good at changing your plans.

As a professional planner and a technology team leader, my role — in large part — is to solicit desires from an array of diverse stakeholders, reconcile them with reality, recommend a plan to deliver on those desires and then implement that plan through a team of talented creators.

In our world, the planning horizon is a calendar quarter, subdivided by months, and further distilled to weeks.

It’s hard work to determine priorities in the first place, build a good plan, and get everyone to buy into it. Once that work is done, new ideas and priorities can feel threatening. And yet, a universal characteristic of stakeholders is that they will change their minds. Priorities, like the weather, shift.

There are many times when I feel compelled to defend a plan from these shifts. How do you listen to a stakeholder’s idea of what they want now while reminding them of what they wanted previously?

Agility is a solution buzzword in software. It’s a buzzword because software teams often get this balance very wrong. Invisible forces drive us to build more detailed and more thorough plans. Over-planning is an industry-wide dysfunction. The opposite problem — rudderless pursuit of every new idea is equally dysfunctional.

Over-planning and under-planning both bring us to the same place: Failure to deliver what matters, on time.

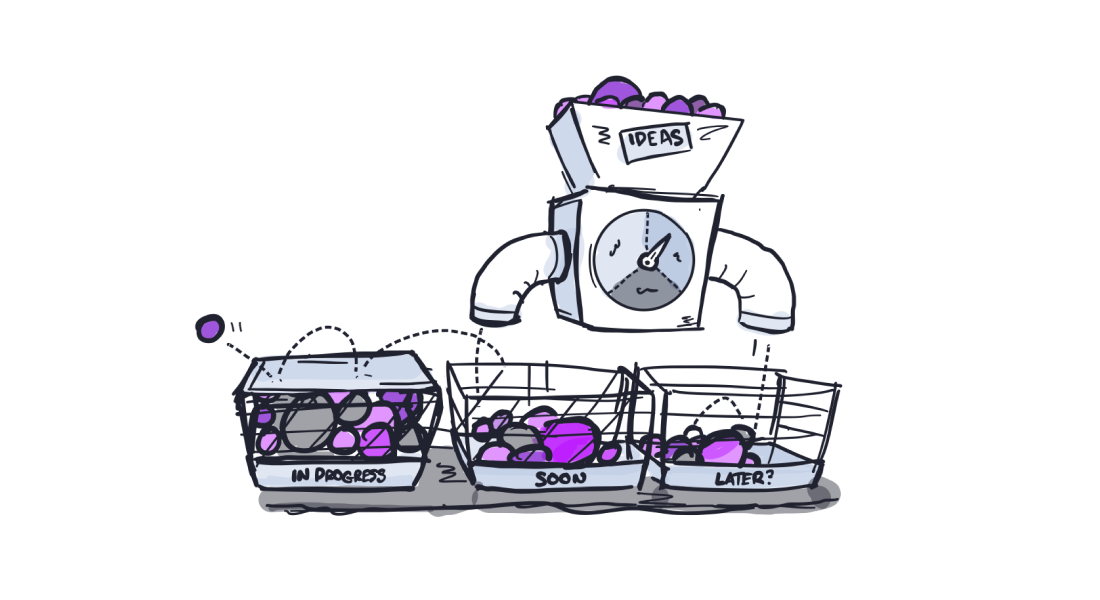

We don’t have it all figured out, but I’m proud of our team’s planning process. We systematically make medium and short-term plans while inviting the continual discovery of new ideas and issues. These new candidates aren’t granted VIP passes to skip the line. They’re filtered at the door with [at least] these two simple questions:

Have our goals changed? Short-term plans were built to serve longer-term goals. This question reveals a couple of things — If we weren’t able to articulate the goal in the first place, it’s hard to articulate a departure from it OR if the goal has in fact changed, then the plan should naturally adapt. Those adaptations may encounter new realities and everyone should prepare themselves to accept that.

When do you really want it? Keep it simple. Use the calendar. Principally, if you want now, you’re changing plans already in motion. If you can wait, even for a short time, then we can make plans around the new requirement.

This scales up or down to whatever time horizon you work at. Need it today? I’m going to have to drop everything else. Can it wait for tomorrow? I’ll plan around it.

The costs of changing plans are not easily quantified. Your dependable, steady software developer who thrives getting “stuck in” to deep problems, may grow to resent you for changing their priorities quickly and often. A designer who needs time to think through a solution, may create a less thoughtful design if you give them a new problem and half the time to adapt. Productivity erodes when we shift contexts.

Business strategy itself will suffer if our process has no mechanism for maintaining longer-term focus. Reactionary fire fighting is an operational necessity, but should be channeled into a mental fast lane, rather than disrupt the steady rhythm of progress.

Change your plans if you need to, but if you find this becoming a habit, ask yourself if there’s opportunity to make them a little differently.